A radical shift in retail architecture

Now that most of our shopping is done online, what are stores for? As Director of Sid Lee Architecture’s Retail Division, architect Alex Dimas is here to answer that question.

Over the last decade, the way we shop has changed radically. Almost anything that’s transactional now happens online, which leaves retailers to wonder what that means for brick-and-mortar stores. It’s an extremely exciting paradigm shift, and one that I think has major societal benefits. Architecturally, it means spaces have to become places that enable meaningful experiences. Think about what life feels like in a village or in your neighborhood: you want to go to your baker, to your barber, to your local café. Retail has to be a part of that social ecosystem in an urban context. At the core, our goal as architects is to create spaces that make people feel good, make them happy and better their lives. That's our contribution to society. And retail is starting to understand that and to align themselves better with that, more and more. The pendulum has swung back to a more human and more authentic experience.

Even the word “consumer” feels dated. Now we say “fans,” and it’s our job as architects to make sure the spaces we create speak to the fans of a brand. We’re all overwhelmed by activities all the time, whether it’s planning our next vacation or our next night out with friends. Where does retail fit into that? We need to give people an experience that speaks to them, that compels them to go out and take part in it. What we do now is much closer to hospitality.

Every store is a lab

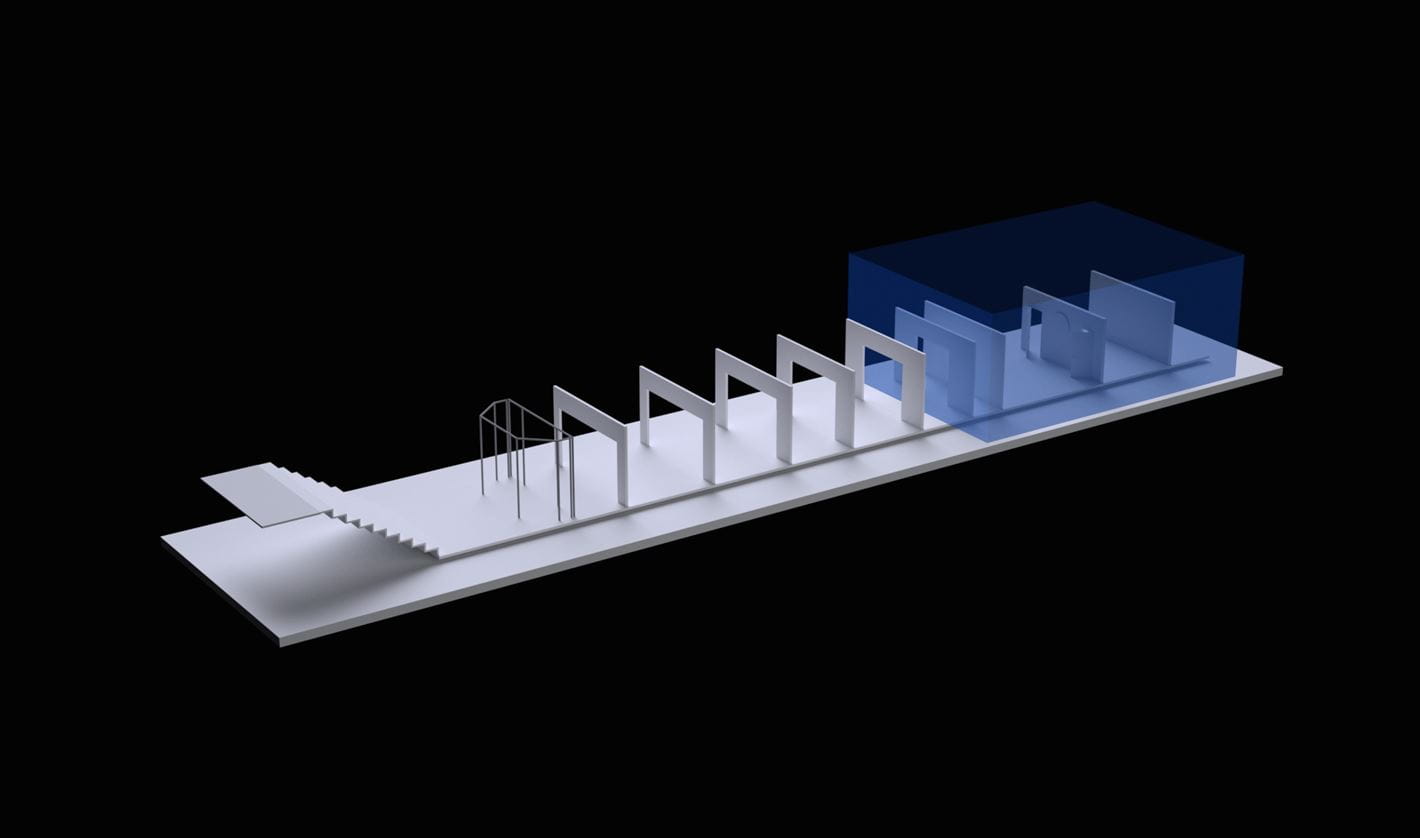

The way architecture responds to that shift now is with a narrative. It’s not enough to just design a space to make it look good. Before we begin any kind of architectural design, we do anthropological and ethnographic research to develop a strategy. Context is crucial, and the idea of a roll-out philosophy is dead. The way you have to approach the new retail paradigm is by thinking that every store is a lab. You have to consider what the context and community around a space are giving you, and give it a unique identity based on that.

One brand that understood this shift really early on was Starbucks. They established themselves as the third central destination—between home and work—in people’s lives. They instantly understood that they had to create a destination rather than a shop. They tap into the smell, the feeling, the mood, the lighting. They created comfort and made spaces that feel like a second home. A more recent example is the launch of Apple’s town square retail concept in Chicago, a sleek riverside space for people to gather, hear speakers, take workshops, and socialize. “This is not a store,” one of the architects said at the time. “It’s an urban renewal idea.”

The death of the mall

It’s a little bit tricky to pinpoint when this paradigm shift happened, but people were already calling the near-death of malls in 2016. It was the first time in more than 30 years that malls didn’t experience expansion. Back in the ‘80s, malls were the central social gathering place for people and really changed the urban landscape in a negative way, in a lot of cases. Take the third season of Stranger Things, for example: it’s 1985, the mall has just opened, and that’s where everyone is hanging out, which means other local businesses are shutting down. You really see how malls killed small towns. Now brands want to be on the street and in contact with people in the community. Architecturally speaking, the historical examples that come closest to the kinds of spaces we’re thinking about are churches, arenas and schools—the places that have acted as social gathering spaces for the community. And those are the kinds of spaces brands are now trying to emulate.

One of the biggest challenges we face in retail architecture right now is staying current. In the digital world, you can change a platform in three to six weeks. Brick-and-mortar, in its quickest execution, can be redone in six months. So once it’s built, the concept is already six months old. To mitigate this, we give ourselves some flexibility in our designs. Maybe we’re doing a centre bar, but the bar can move, or we have wall panels that can be switched around or removed. Lighting makes or breaks a space so we play with that, adding dimmers or creating different areas where the lighting casts a different mood. To stay relevant, you need to look at your entire ecosystem: the brand, the digital representation, the experience, and the space. Take one ingredient out of the recipe and your cake won’t taste as good.

Make emotional connections

It's essential to curate a retail space that really speaks to people. You have to develop a unique identity and make emotional connections, not only with the fans but with the staff. They’re the ambassadors of the brand, the people who are carrying the message, and the space needs to speak to them too. Online, customers can read instant, unfiltered and honest reviews of millions of products. A brand needs to offer that transparency and authenticity too, whether it’s Aesop describing where their product ingredients come from or Frank And Oak detailing how their materials are made sustainably.

The diversity of values in millennial culture is also something our retail teams and brands are contending with. With the onset of technology and social media, millennial priorities aren’t as clear as in generations past. For some, their main value could be being eco-friendly. For others, it could be products made locally. Others still might hold price point as most important, while another group could take a more philosophical approach. So brands can’t use a one-size-fits-all framework anymore. And for us, it begins with asking the right questions from the start. Why does this store exist? What is its purpose?

People don't buy things—they covet them

Two years ago, Sid Lee did a retail collaboration between adidas and Concepts International, a Boston-based sneaker company, in the basement of a space on a high-end street in Boston. The space itself was hole-in-the-wall tiny—just 700 square feet. But as we delved into the research, we learned that the sneaker subculture is enormous. There are diehard sneaker fans who might never wear a shoe but live to say that they own it, and sneaker brokers who come in to buy the shoes and drive up prices. We realized that the small space would work to the store’s—and the community’s—advantage. Hundreds of people lined up outside, from parents with young kids to teenagers to fans in their 40s and 50s. It created an event on the street, stoking curiosity from passersby and encouraging people to talk to one another.

We were commissioned to do a second store for them, and a few months ago I presented the second project to the city of Boston for approval. After the presentation, a grey-haired woman in her mid-60s approached me. “Did you guys design the store at 73 Newbury?” she asked, and I said, “Yes, that was us.” She held out her feet to show me her sneakers. “I love that store!” To me, that was mission accomplished. The idea that a store and its design can create links, social gatherings, and social interactions is so powerful. It’s the history, the story, the narrative behind a space that really elevates it. We’re trying to create a sense of reverence. People don’t buy things. They covet things. If you understand that difference, then you’re going to have a positive societal impact.